- What is a Cog Railway?

- History of the Pike's Peak Cog Railway

- Swiss Trains

- Snow

First off...what is a "Cog" Railway?

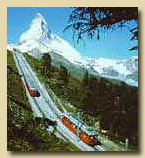

Conventional railroads use the friction of wheels upon the rails, called "adhesion", to provide locomotive power. A cog, or rack, railroad uses a gear, "cog wheel", meshing into a special rack rail (mounted in the middle between the outer rails) to climb much steeper grades than those possible with a standard adhesion railroad. An adhesion railroad can only climb grades of 4 to 6%, with very short sections of up to 9%. A "rack" railroad can climb grades of up to 48%, depending upon the type of rack system employed. Some Swiss trains use a combination of "rack" and "adhesion". This enables the trains to reach much higher speeds on the adhesion sections (rack railroads can not go much faster than 25 miles per hour or they run the risk of dislodgement from the rack rail- M & PP Ry.'s top speed is about 9 MPH).

Conventional railroads use the friction of wheels upon the rails, called "adhesion", to provide locomotive power. A cog, or rack, railroad uses a gear, "cog wheel", meshing into a special rack rail (mounted in the middle between the outer rails) to climb much steeper grades than those possible with a standard adhesion railroad. An adhesion railroad can only climb grades of 4 to 6%, with very short sections of up to 9%. A "rack" railroad can climb grades of up to 48%, depending upon the type of rack system employed. Some Swiss trains use a combination of "rack" and "adhesion". This enables the trains to reach much higher speeds on the adhesion sections (rack railroads can not go much faster than 25 miles per hour or they run the risk of dislodgement from the rack rail- M & PP Ry.'s top speed is about 9 MPH).

The first cog (or "rack") railway was built in New Hampshire in 1869,

but the Swiss were quick to make use of this technology, and numerous rack railways were built there. Indeed, Switzerland is still the country where most rack railways are located. The Manitou and Pikes Peak Railway is, however, the highest rack railway in the world as well as the highest railway in North America and the Northern Hemisphere. The M&PP Ry. has a perfect safety record!

Indeed, Switzerland is still the country where most rack railways are located. The Manitou and Pikes Peak Railway is, however, the highest rack railway in the world as well as the highest railway in North America and the Northern Hemisphere. The M&PP Ry. has a perfect safety record!

The Manitou & Pikes Peak Railway uses the Abt rack system. The maximum grades are 25%, which is about the upper limit for the Abt system. Many rack railroads use the Riggenbach system, also called "ladder rack". The steepest cog railway in the world is the Mt. Pilatus Railway in Lucerne, Switzerland. It uses the Locher rack system to climb grades of 48%!

History of the Pike's Peak Cog Railway

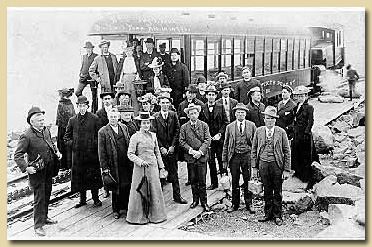

One of the tourists who visited the Pikes Peak region in the late-1880's was Zalmon Simmons, inventor and founder of the Simmons Beautyrest Mattress Company. Mr. Simmons rode to the summit of Pike's Peak on a mule, partly to enjoy the view and partly to check upon one of his inventions: an insulator for the telegraph wires which ran to the Army Signal Station on the summit. The arduous, two day trip on a mule was the only way to reach the top in those days. Mr. Simmons was awed by the scenery but determined that the views should be experienced in a more civilized and comfortable manner. He was relaxing in one of Manitou Springs' mineral baths after his return, when the owner of his Hotel mentioned the idea of a railway to the top. Mr. Simmons agreed with the concept and set about providing the capital needed to fund such a venture.

One of the tourists who visited the Pikes Peak region in the late-1880's was Zalmon Simmons, inventor and founder of the Simmons Beautyrest Mattress Company. Mr. Simmons rode to the summit of Pike's Peak on a mule, partly to enjoy the view and partly to check upon one of his inventions: an insulator for the telegraph wires which ran to the Army Signal Station on the summit. The arduous, two day trip on a mule was the only way to reach the top in those days. Mr. Simmons was awed by the scenery but determined that the views should be experienced in a more civilized and comfortable manner. He was relaxing in one of Manitou Springs' mineral baths after his return, when the owner of his Hotel mentioned the idea of a railway to the top. Mr. Simmons agreed with the concept and set about providing the capital needed to fund such a venture.

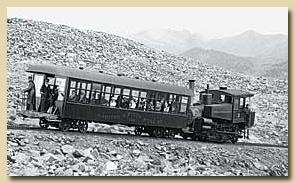

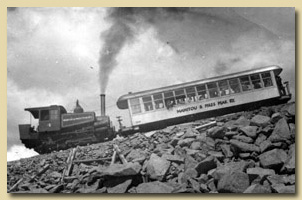

In 1889, the Manitou & Pike's Peak Railway Company was founded and track construction began in earnest. Top wages were 25 cents per hour. Six workers died in blasting and construction accidents. The Age of Steam predominated the late 1800’s, and from Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, three engines were delivered in 1890. Limited service was initiated in that year to the Halfway House Hotel . These locomotives were eventually converted to operate upon the Vauclain Compound principle, and a total of six were in service during the "steam" era. The original three were named "Pike’s Peak," "Manitou" and "John Hulbert," but they soon were assigned numbers. Of the original six, only #4 is still in operation and along with a restored coach makes infrequent trips short distances up the track.

The spring of 1891 was a snowy one, and the opening of the line was delayed until late June. On the afternoon of June 30th, 1891, the first passenger train, carrying a church choir from Denver, made it to the summit. A scheduled group of dignitaries had been turned back earlier by a rock slide around 12,000 feet. The railway was now operating.

The spring of 1891 was a snowy one, and the opening of the line was delayed until late June. On the afternoon of June 30th, 1891, the first passenger train, carrying a church choir from Denver, made it to the summit. A scheduled group of dignitaries had been turned back earlier by a rock slide around 12,000 feet. The railway was now operating.

A new era began in the late 1930’s with the introduction of gasoline and diesel powered locomotives. Spencer Penrose, owner of The Broadmoor Hotel, had acquired the Railway in 1925 and efforts were begun to build a compact, self-contained railcar, which could carry fewer passengers during the slow parts of the season. These efforts culminated in No. 7; a gas-powered, 23-passenger unit, which made its first run on June 16, 1938. It is believed that No. 7 is the first rack railcar ever built in the world.

The experiment was a huge success, and within a year of No. 7’s introduction, No. 8, the world’s first diesel-electric cog locomotive, was delivered from the General Electric Company. Coupled with "Streamliner" coaches, No.s 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 formed the backbone of the Railway’s fleet in the period from 1940 through 1965. The coaches could carry 56 passengers in comfort and style, and the diesel locomotives eliminated the time-consuming water stops as well as the back-breaking job of shoveling coal.

The experiment was a huge success, and within a year of No. 7’s introduction, No. 8, the world’s first diesel-electric cog locomotive, was delivered from the General Electric Company. Coupled with "Streamliner" coaches, No.s 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 formed the backbone of the Railway’s fleet in the period from 1940 through 1965. The coaches could carry 56 passengers in comfort and style, and the diesel locomotives eliminated the time-consuming water stops as well as the back-breaking job of shoveling coal.

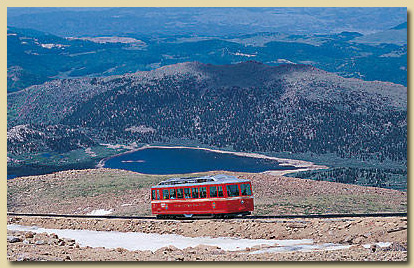

The modern age of the Manitou and Pike’s Peak Railway began with the requisition of railcars from the Swiss Locomotive Works in Winterthur, Switzerland. In the early 1960’s, as tourism began to increase in Colorado, the Railway needed additional equipment, but the General Electric Company was not interested in the project. Mr. Thayer Tutt, President of the Railway, traveled to Switzerland to arrange for the modern railcar acquisitions.

The first units to arrive from Switzerland were Nos. 14 and 15, which were put into service in 1964. They proved so successful that soon after, the Railway ordered two more nearly identical units, Nos. 16 and 17. These Swiss railcars are self-contained units, powered by two Cummins diesel engines mounted underneath the seating area. As with the GE locomotives, they are diesel-electric. Generators driven by the diesel engines provide the power to traction motors for the ascent. For the descent, the diesel engines are shut down and the traction motors work as generators. The electric power generated is consumed by resistor banks on the roof of the railcars.

The first units to arrive from Switzerland were Nos. 14 and 15, which were put into service in 1964. They proved so successful that soon after, the Railway ordered two more nearly identical units, Nos. 16 and 17. These Swiss railcars are self-contained units, powered by two Cummins diesel engines mounted underneath the seating area. As with the GE locomotives, they are diesel-electric. Generators driven by the diesel engines provide the power to traction motors for the ascent. For the descent, the diesel engines are shut down and the traction motors work as generators. The electric power generated is consumed by resistor banks on the roof of the railcars.

A young Swiss engineer, Mr. Martin Frick, was also hired from SLM at this time. Over the next 30 years (until his retirement in 1991), Mr. Frick brought the Railway into the modern age. The Railway is deeply indebted to Mr. Frick for the years of his dedication and hard work. In addition to the first 80 passenger railcars, he did a major expansion of the shop facilities, oversaw the installation of new, modern switches in the yard (electric) and along the line (manual), designed and built (with the assistance of our shop personnel) snowplow #22, helped with the design and supervised the acquisition of four 214-passenger railcars and many other improvements too numerous to mention. Mr. Frick (as of April 2005) continues to help with Swiss and German transactions and offers expert advice. Once again, thank you Martin for your love of the Railway.

Bigger units were needed as tourism continued to grow into the 1970’s. The Manitou and Pike’s Peak Railway officials returned to Swiss Locomotive Works in 1974 with a request for a train which could carry over 200 people. The results were the articulated railcars Nos. 18 and 19. These cars resemble the smaller single units but are joined by a bellows in the middle. A key difference is that they are diesel-pneumatic. The braking is done through a pneumatic retardation system, and the diesel engines must idle on the return trip. These first two modern railcars were put into service for the 1976 season; No. 24 was added in 1984 and No. 25 in 1989. As an adjunct to the arrival of the first big Swiss railcars, new switches were installed along the line. Prior to 1976, trains departed the Manitou depot only three times a day in the summer. The equipment needed to transport the number of passengers at the depot was brought down from the shop, loaded up and arrived together at the summit. With the sidings which were added at Minnehaha and Windy Point, trains can run up to eight times per day and pass along the line. Now, trains depart in mid-summer every eighty minutes, from 8:00 AM until 5:20 PM.

Bigger units were needed as tourism continued to grow into the 1970’s. The Manitou and Pike’s Peak Railway officials returned to Swiss Locomotive Works in 1974 with a request for a train which could carry over 200 people. The results were the articulated railcars Nos. 18 and 19. These cars resemble the smaller single units but are joined by a bellows in the middle. A key difference is that they are diesel-pneumatic. The braking is done through a pneumatic retardation system, and the diesel engines must idle on the return trip. These first two modern railcars were put into service for the 1976 season; No. 24 was added in 1984 and No. 25 in 1989. As an adjunct to the arrival of the first big Swiss railcars, new switches were installed along the line. Prior to 1976, trains departed the Manitou depot only three times a day in the summer. The equipment needed to transport the number of passengers at the depot was brought down from the shop, loaded up and arrived together at the summit. With the sidings which were added at Minnehaha and Windy Point, trains can run up to eight times per day and pass along the line. Now, trains depart in mid-summer every eighty minutes, from 8:00 AM until 5:20 PM.

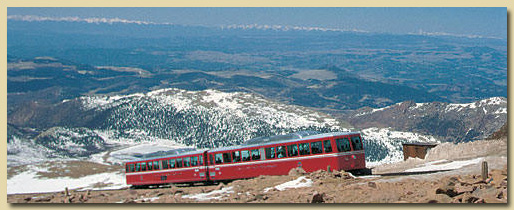

In the early days of the Railway, snow was a huge problem. Most of the snow falls on Pikes Peak in the spring, and the Railway cannot open until the line is cleared. Removal was a lengthy and exhausting task involving little other than muscle power. A steam engine would ram a flat car outfitted with a wedge on its nose into the massive banks of snow that had been loosened by charges of dynamite. The section crew would shovel as much additional snow as possible onto the flat car which would then back down to the nearest available opening. The "gandy dancers" would shovel off the snow, and the whole process would be repeated. From timberline to Windy Point, drifts up to 15 feet are normal, and the job was slow and time consuming. For many years, the line was not fully open until June (for the opening season of 1891, it was not open until June 30th). Even today, it is not uncommon to have an overnight storm completely cover the deep cuts below Windy Point with a new blanket of snow.

In 1953, rotary snowplow No. 21 was constructed in the Railway shops in an attempt to open the line earlier. This early plow, however, met with only limited success. The unit was plagued by mechanical difficulties and subject to easy dislodgment from the rack rail. Much of the time the old wedge plow, powered by diesel locomotive No. 9 or No.11, would be responsible for the lion’s share of the work in opening the line.

The spring of 1973 was one of the worst in the Railway’s history. Snowstorm after snowstorm pummeled Pikes Peak, and the line was open for only two days in May. Even on days of sunshine, winds would blow the huge drifts above timberline and fill in the cuts overnight. The next morning, returning workers would arrive back at timberline to find the previous day’s gains wiped out. Railway management decided that a new plow, using thoroughly modern technology, was needed. The next winter was spent constructing No. 22, the current snowplow. This massive unit, powered by a 500 horse-power, 12-cylinder Cummins diesel engine, today enables the Railway to open after all storms and stay open through the big snowstorms of April, May and early June (April and early May are usually the snowiest months).